"Zero percent healthy:" How the genocide in Palestine has changed everything about food

A conversation with writer Lama Obeid about on systematic attack on food, foodways and nutrition in Palestine that works alongside tactics of starvation and hunger.

Ramallah-based culture writer Lama Obeid finds that the genocide has brought about a paradigm shift - not only in the realms of cookery, cookbooks and recipes, but also in the very food that Palestinians are being made to consume.

The attack on food, foodways, health and nutrition is sustained, deliberate and systematic, and works alongside tactics of starvation and hunger. Not only is there widespread scarcity, but the food that is available is processed, unhealthy and acts as slow poison.

Lama begins by explaining the disruptions in the food supply chain amid frequent raids in the Jenin refugee camp, for example, and Palestinian cities being cordoned off from one another. The immediate effect of this is that Israeli produce proliferates in the market, and often these foodstuffs turn out to be settlement products that are labeled as Israeli. The genocide in Gaza has completely collapsed the existing system. Even during the 18 years of brutal blockade, Gaza produced its own food. Strawberries, tomatoes, cucumbers, seafood and other produce was even allowed from Gaza into the West Bank.

“Especially the strawberries,” Obeid says. “It’s an alternative to the Israeli strawberries. We do have some strawberries growing in the north, but the climate in Gaza is more suitable.”

Over the last two years, fresh produce has become a priceless commodity. Processed food is everywhere, and Lama reports that, in addition to canned beef and beans, which have been a staple of UN rations, “unfortunately, there are things that even I’ve never seen canned before.”

Lama is horrified about the distribution of canned boiled eggs and canned chicken, for example, all of which are probably “zero percent healthy.”

Another way to ensure Palestinians have no access to fresh produce are Israeli settler attacks on olive farms. These farms, often small in size, can sustain entire families.

Palestinian food was always political. Cookbooks often emphasize the impact of the longstanding occupation and attempt to preserve and archive recipes with a sense of urgency - archiving under fire. But the sense of urgency has become the norm, and the genre of the traditional cookbook has been replaced by something different - food bloggers and writers who double up as journalists reporting on the genocide using food as lens. Mona Zahed’s book Tabkha is actually subtitled Recipes from Under the Rubble. Lama reminds us that Zahid from Gaza was displaced with her family and “wrote this cookbook during her displacement to document also the family recipes, and also to try to support her family.”

The documented recipes in Tabkha work against erasure in terms of archiving the heritage, but the cookbook is also a way for her family to literally survive the imminent threat of erasure.

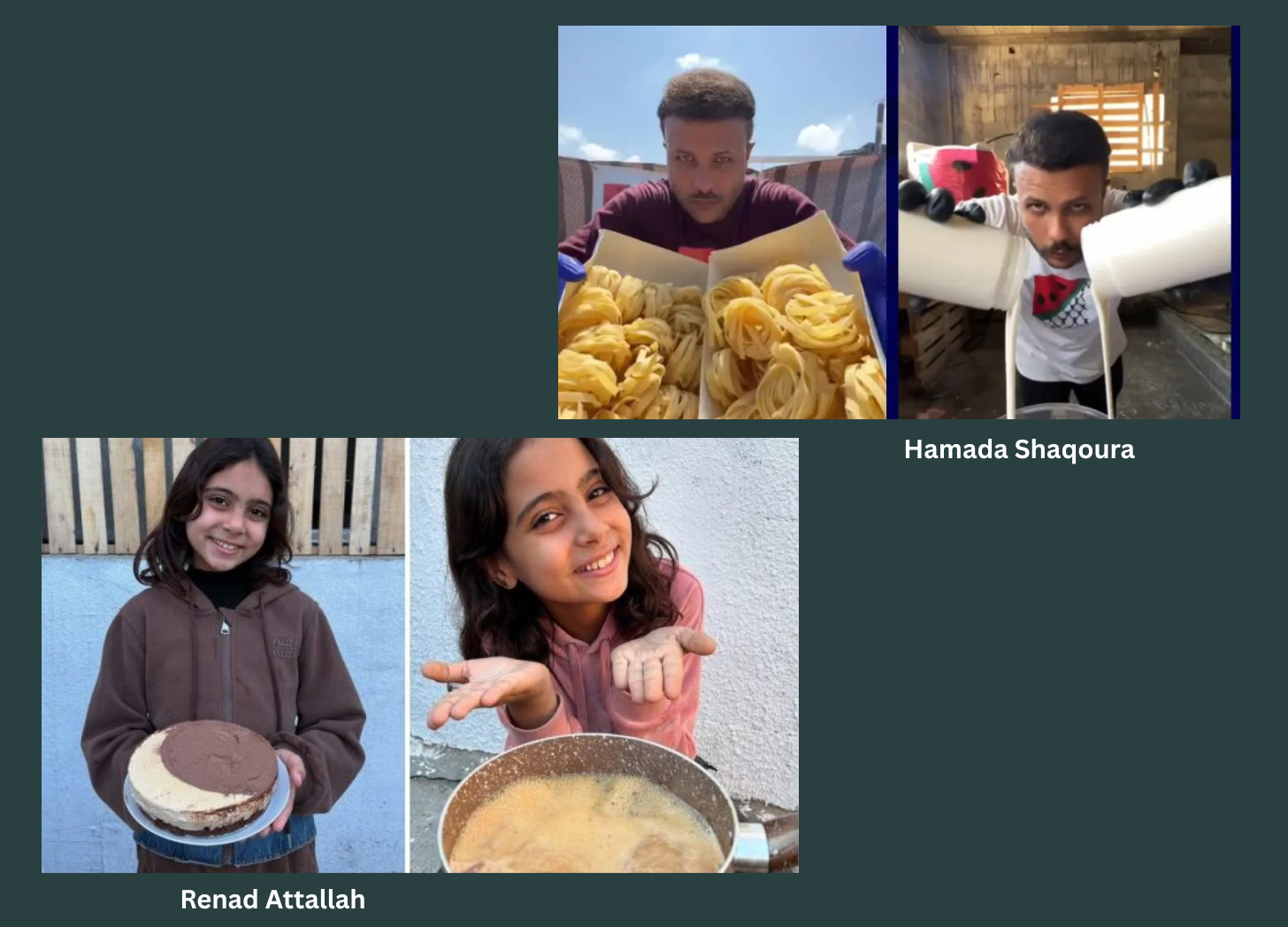

Food bloggers have become popular over the course of the two-year genocide, and many use these platforms to raise funds for their families. Renad Atallah was only 9 years old when she gained a large following after making cooking videos, smiling radiantly even as bombs rained down and ingredients became more and more scarce. Similarly Hamada Shaqoura began posting videos of himself cooking and distributing food to children. His videos have a tongue-in-cheek humor as he glowers at the camera while stirring vats of food. His humorous affect alongside images of large quantities of food work against the stereotypes of wretchedness and emaciation.

Palestinian cuisine and gastronomy are no longer confined to preserving heritage or exploring culinary tradition, but rather are about capturing the nitty-gritty of survival in wartime. Lama points out that, even as these chefs write or blog about these recipes, they have no ingredients to actually make them, and they “unfortunately, are not eating these recipes. So what is being documented now in Gaza are the basic staples, very basic staples, and what we would call ‘war food,’ or the food made from rations.”

There are very few silver linings, but at a time where everything and everybody have been exposed, Lama is relieved to note that there is no tolerance for the ways in which Palestinian food is appropriated and normalized as Israeli food. Israeli chef Yotam Ottolenghi, for example, has collaborated with Palestinian chefs, thus giving the impression that this is one cuisine and one shared heritage and thereby obscuring the violence of the occupation. But now, Lama says, such collaborations have stopped.

As a third generation Palestinian refugee displaced from the town of Ein Karem in West Jerusalem, Lama continues writing about food with a proudly Palestinian and sharp, political lens. Lama is fatigued by the Israeli-Palestinian debates around food and believes that the solution lies in turning her gaze to the past and diving into many untranslated Arabic works about food, because Palestinians have always made attempts to “record their own cuisine.”

Follow Lama Obeid’s writing below:

Love and solidarity❤️🔥

Bhakti Shringarpure

Fuckin dirty muzzrats